One book that should probably never be written is Power Distro for Dummies. Given the high voltages in play where power distribution is concerned and the danger of physical harm, it’d be a better idea if dummies stayed out of the electrical room and left electrical work to licensed electricians. However, there are certain things about power that audio people need to know, and though we do not suggest that you attempt adding a new circuit breaker box to a venue unless you are a licensed electrician, it might make your life easier if you knew a bit regarding power distro requirements.

How Much Is Enough?

Let’s start with a basic question that can easily and safely be answered on paper: How much power does my audio gear need? It’s a fair question and you’ll need the answer whether you are traveling with a P.A. or spec’ing a system for a new venue.

Power is expressed in watts. Typically the power requirements of an electrical device can be found on its rear panel near the power inlet — whether it’s an IEC receptacle or a captive AC cable. If not, consult the manual. AC power requirements for devices using line lump or wall wart power supplies will usually be found on the device itself. And if there is no information regarding power consumption either on the rear panel or in the manual, have a look at the device’s fuse or circuit breaker. Its value is the maximum current that the device can ever consume.

In theory, all you need to do to determine the total system power consumption is find the wattage requirements for each device and add them. Ahh, but as we always say in these pages, theory is not practice. The power requirement for a piece of gear is almost always expressed in watts, but electrical circuits are almost always rated in amps, as in amperes. The reason behind this is that the supplied AC voltage might vary to run something like a 240-volt air conditioner, but the device may still require the same amount of power.

Feed Me

Let’s take a look at a simple, real-world example. Suppose you have a power amplifier that consumes 1,500 watts and you want to plug it into an AC outlet near a stage. How do you know that outlet is capable of safely supplying power to the amp? Well, one way is to plug in the amplifier, turn it on and see what happens — but that’s too much of a mystery, and I don’t like mysteries. They give me a bellyache. If the amp does not turn on, you won’t know why. If it does turn on, it may not stay on all night.

You need more information, so you look at the electrical panel housing the circuit breakers that feed the various AC outlets in the venue. A circuit breaker is an automatic switch designed to open (disconnect) when current exceeds a certain level. It is tolerant of passing enough electricity that it knows the subsequent wiring can handle safely.

Assuming the person who installed the electrical service was diligent, all of the circuit breakers will be clearly labeled. You find one labeled “next to stage” and see that it’s rated “15 amps.” But your power amp is rated 1,500 watts.

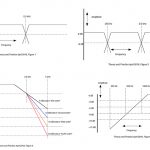

You need a way to convert watts to amps, and we have a formula for it. That formula states: “Power (P, in watts) equals voltage (V) multiplied by current (I)” or

P = V x I

If we divide both sides of this equation by V, we have

P/V = I

or “power divided by voltage equals current.”

Given any two of these values, you can find the third.

We know the power requirement of the power amplifier because we found it on the rear panel (1,500 watts).

Voltage (V) in the US is 120 volts (+/- a few percent. We’ll use 120 to keep the math simple.

(I’m a little burnt from converting between Euro, Swedish Krona and USD).

To calculate I…

P/V = I

1,500 watts/120 volts = I

1,500/120 = I

12.5 amps = I

Our power amplifier needs 12.5 amps to operate properly — well below the rating for that circuit (15 amps).

If we were in the U.K., our voltage would be 240 (technically, it’s supposed to be 230 volts, but in fact it’s still often 240).

Assuming that our power amp can be switched to accept the higher voltage…

P/V = I

1500/240 = I

6.26 amps = I

Current required in the U.K. for that same power amp is exactly one half that of the U.S. because the voltage has doubled. Power consumption remains the same: 1,500 watts.

There are a couple of things we need to pay attention to here. Audio devices (particularly power amps) require more AC as they work harder to produce higher output. That power amp may work on a 10 amp circuit, but when you crank it up to its maximum volume, it wants 12.5 amps. Meanwhile, a 10 amp circuit (which should have been outfitted with a 10 amp circuit breaker) will blow when the amplifier is cranked, even though it worked fine when the amp was “idling.”

Some manufacturers of power amplifiers will state the power consumption in amperes, sparing you the time to do the calculation. This is very important, because not only do you want to avoid blowing breakers in the middle of a show, you also want the gear to deliver the best audio quality possible.

Second, we made an assumption that the power amp was the only device being powered by this particular electrical circuit, and that may not be the case. You need to know what else is being used on the circuit (maybe it’s the dishwasher. Don’t laugh).

Third, if your P.A. system employs more than one power amplifier (or powered speaker), you’ll need to find another AC outlet with its own circuit for the second power amplifier.

Now that you understand the math, you can intelligently answer a question such as “what are the electrical requirements of your audio system?”

Here’s a quick example:

Digital console for house: 250 watts

Digital console for monitors: 250 watts

Four power amps for stereo biamped mains speakers: 1,750 watts each; 7,000 watts total

Two power amps for four channels of stage wedges: 1,250 watts each; 2,500 watts total

Four wireless IEM systems — 20 watts each: 80 watts total

Two wireless microphones — 30 watts each: 60 watts total

If we add the power requirements we come up with a total of 10,140 watts.

Plugging that number into our formula P/V = I, we get:

10,140/120 = I

84.5 amps = I

Our audio system requires 84.5 amps of electrical service, most of which is sucked up by the power amps. This system can be easily powered by 100 amps of electrical service, but if we were consulting on an install for a new club, we’d be wise to advise the venue owner to bring in 200 amps of electrical service dedicated to the audio system. When they upgrade the P.A. system in two years, they won’t need to revise the electrical service so you’ll look like a genius. Note that this does not include power for the backline, and it certainly does not include lighting, which should have an independent supply.

It’s worth mentioning that the power consumption for a power amplifier is not the same as its audio output. Power amps are generally rather inefficient devices that suck up more electrical power than they produce, in terms of audio power. Amps designed for pro audio tend to be among the most efficient (better than 50%), but some of the lunatic fringe Class-A power amps for home hi-fi gulp down 1,500 watts of electricity to produce 25 watts of audio power. They also serve as excellent space heaters.

Portable Distro

Now let’s suppose that you are bringing this P.A. into a venue and need a way to safely distribute power to your gear. Here’s a bad idea: bring a bunch of orange extension cords and quad boxes. Here’s a good idea: carry a portable power distro so you don’t have to chase down separate circuits for your amplifiers. A portable power distro is a compact power distribution box that gets connected to the house electricity and provides one convenient point for AC supply, one of the benefits of which is reduced possibility of ground issues. For these types of distros “gets connected” means a variety of things that we’ll discuss next month, but it does not mean “attempt to tie the distro into a nearby AC transformer or service junction” — which should be done only by a licensed electrician. A portable distro can provide up to several hundred amps, with multiple AC outlets and circuit breakers on a single convenient panel.

Next month, we’ll look at some specific portable AC distro systems that can keep your gear happy while preventing you from getting zapped.

For more info regarding power distribution, see Phil Graham’s articles in the October and November 2013 issues of FRONT of HOUSE.