Many small venues don’t have the budget or space for a separate monitor desk on stage. That saddles the front-of-house engineer with the responsibility of mixing for the band and the audience simultaneously from the FOH console — not an easy task. Here are some suggestions that can help alleviate your pain.

The first part of mixing monitors from front of house is having monitors. I’m not kidding. A common mistake in small venues is setting the house speakers on stands behind the band, so they can use the PA as monitors. This is a bad idea: It’s a recipe for feedback; EQ is the same for the audience as for the musicians; and any effects added to the house regenerate through the vocal mics.

» Send Me a Greeting

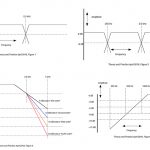

One of the most important considerations when mixing monitors from FOH is knowing which (if any) of the console’s aux sends are pre- or post-fader. Let’s review a bit of signal flow and look at Fig. 1, a stripped-down road map of an input channel. Signal flows from left to right. The mic connects to the XLR input on the far left and routes to the preamp and trim control. It then passes the insert send/return, EQ and channel fader (phase reverse and high-pass filters are omitted for clarity). After the channel fader, the signal goes to the bus assignment and makes its way to the L/R master bus. Aux sends tap the signal at several possible points. Take a look at point A on the right. This is where a post-fader send is taken. You don’t want to send a signal to a monitor mix from this point, because whenever you move a fader to adjust the house mix, the monitor mix also changes.

It makes more sense to take an aux send for monitors before the fader, such as the point labeled B. Note that it is pre-fader. You can move the fader or even bring it down completely and the monitor mix will not change. This is a good thing. It means you can mix-to-taste at front-of-house and not disturb the musicians any more than they are already disturbed. While we’re here, determine whether the channel’s mute switch also mutes the send. How do you know? Try it or check the block diagram in the console manual.

Now that we understand the difference between pre- and post-fader, we can address the EQ and insert. Consult the manual and get answers to the following questions regarding the pre-fader aux send(s): is the pre-fader send also pre-EQ? Is it pre-insert?

Why do you care, anyway? Let’s suppose that an aux send is pre-fader. In an ideal world, this send is also pre-EQ and taken from point C in the diagram, allowing you to EQ the channel to taste in the FOH mix without changing the EQ on the signal going to the monitor mix. A pleasing EQ in the house mix may cause feedback in the monitor(s). Or vice-versa: EQing a particular for reduced feedback in the monitors may cause it to sound weird in the house mix.

Hardware (and sometimes software) inserts are typically right after the mic preamp. This becomes a concern when a compressor is inserted. Think about it. Your lead vocalist wails like Axl Rose in one song and whispers like Sarah McLachlan on the next song, so you’d like to use a compressor on the vocal channel to tame the dynamics. This is a good idea, but — if the monitor send is taken after the insert (as shown by letter C), it means you are also compressing the vocal in the monitor mix, which can promote feedback. Ideally the monitor send is before the insert (letter D), so you can compress the vocal in the house and not create feedback in the monitors.

Note that most consoles place the pre-fader aux sends post-insert. Got that? Grrrr. Solution: Be conservative with the amount of compression. This same concept works in your favor on drum channels. It can be very helpful to have a gate inserted before the monitor send, so kick, snare and tom mics are gated in the monitors as well as house, reducing the spill and phase cancellation caused by open mics.

» Equalized Opportunity Employer

The typical 3-band sweep EQ found on an input channel isn’t of high enough resolution to tune monitors. We need another way to EQ the monitor mixes, and that’s where a graphic EQ comes into play. Plan on having one channel of 31-band graphic EQ for every monitor mix. The console’s aux send master output is patched into the EQ, and the output of the EQ is patched into a power amp for the monitor (or the input of a powered speaker). Unless your console is digital and supports network control via iPad or tablet, EQing monitors generally requires an assistant onstage. Use a talkback microphone to communicate with them. Patch a mic into a spare input channel, remove it from the L/R bus, and route it to the same aux send used for the monitor. Now your assistant can hear you through the wedge, saving you the grief of screaming at them while the opening act’s drummer tunes her kit.

Ringing out monitors is a topic for another time, but for now what we are trying to accomplish is using the graphic EQ to remove feedback-prone frequencies from the monitor(s). Unfortunately, those frequencies vary with the type of monitor, the microphone, reflectivity of the stage, temperature and humidity, so you’ll have to try to find them through careful listening or a handheld RTA. Slowly bring up the aux send so that your assistant can hear their voice. When you hear the onset of feedback, try to find the frequency on the ‘graph that is ringing and pull it out a bit.

Consistency on the stage is your friend, especially if you are providing only one monitor mix (meaning there’s one EQ) that is fed to multiple wedges for various musicians. Try to make all of the monitors the same brand/model. That way, their EQ requirements will be similar, so if you get one to sound pleasing, then (hopefully) they’ll all sound pleasing. Ditto for the microphones. Different mics create varying frequency responses in the monitor(s), which will require unique EQ curves to avoid feedback. If the mics are all the same, at least you have a chance in achieving an EQ that corrects feedback from more than one mic.

» Other Advice

Encourage the band to keep their stage volume down, which gives you more ability to sculpt their monitor mix(es). As much as possible, encourage the band to fly sans effects in the wedges, because spill from instruments like high-hat will create unwanted echoes in the monitors (unless you are going for that Stewart Copeland high-hat sound).

If the band’s using in-ears, your feedback problems will be greatly reduced, possibly eliminated. You’ll have other issues to address, which we can discuss in a future coffee chat. The signal flow concepts are the same with in-ears, the difference being that you’ll patch the aux send output to the input of the ‘ear system transmitter.

Why Drummers Need Their Own Mix

If the number of available monitor mixes is limited, give the “front line” one mix and the drummers the other mix. Why? Simply due to physical location, the drummer may not be able to hear anything from closed-back guitar/bass cabinets that are plenty loud in front.