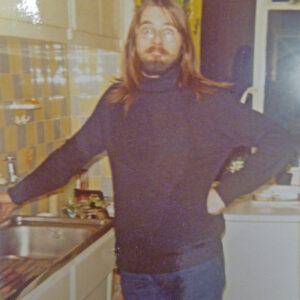

Roy Lamb never thought this concert touring thing could be a “career.” He states emphatically, “Not the slightest idea that this would be my life—absolutely not.” He would be the first child in his family to get accepted to a university, but at that point he was already working with bands. So, he told his parents he was not, in fact, going to college to study economics.

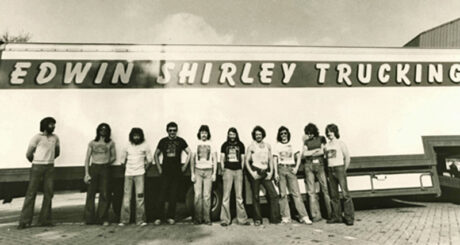

They didn’t talk to him for four months. For five years after that, “they still didn’t have any idea what I did.” They started to get a clue when he was part of the trailblazing Extra Sensory Production (ESP) production company and when he was cofounder of the first industry-specific trucking company, Edwin Shirley Trucking (EST). He would go on to take on pretty much every single role in the live event business, including humble roadie and truck driver, working audio and lighting, and finally, a long stretch as a production manager to stadium-level bands.

His relationships with bands are strong, “but not on a buddy basis—on a technical basis. I’ve always successfully maintained relationships with the artists that I’ve worked for.” Lamb is self-taught, largely making it all up as he’s gone along. And if he didn’t have a direct hand in it, he bore witness to the greatest achievements of the business. “He’s like a live-event industry Forrest Gump,” quips longtime friend and Parnelli Board Chairman Marshall Bissett. “His life intersected with every industry advancement.”

The list of artists he’s worked with includes the Rolling Stones, Pink Floyd, Eric Clapton, Bryan Adams, Keith Richards, Robert Plant/Jimmy Page, R.E.M., the Cars, and many others. “Over 40 years ago I recommended Roy for a job as production manager for The Who,” says Brian Croft, the first recipient of this award. “[Manager] Bill Curbishley said, ‘Yeah, I like Roy, but I didn’t know he was a production manager.’ Which he wasn’t. “‘Bill,’ I said, ‘Roy’s good at everything.’ Roy got the gig of course.” That was 1981, and he’s been with them ever since, including the most recent tour that wrapped up this past October. It’s for this and so much more that he’ll be receiving the industry’s highest honor, the Parnelli Lifetime Achievement Award, on April 14, 2023, in Anaheim, CA.

“This Kid Is Sharp”

Lamb was born in London in 1950 and grew up in the Wandsworth district. In England’s equivalent of high school, he got involved with the drama society, “which was a skive [shirk] because it meant I didn’t have to go to lessons,” he says with a grin. It was there he was drawn to the technical aspects of theater, building sets and running lights for four productions a year. When it was time to graduate, the head of the English department told him about the National Youth Theatre. Founded in 1956, it was the world’s first national theatrical summer program for youth. One student who went through the program was Brian Croft, who was back doing a show for the school after he had graduated. “I first met 17-year-old Roy on an intercom system as he was going to be the board-op on a production of Macbeth at the Roundhouse in 1969,” Croft says. “I had been up all night supervising the rig. Roy had come in at dawn, way before he was called. We started plotting during rehearsals later that morning as they were doing different scenes on stage. Roy seemed to be totally in tune with my mumblings and plotted incredibly quickly. I thought, ‘This kid is sharp and will go places.’”

“I fell in love with it all when we did Macbeth, and I ran the desk and the lights,” Lamb says. At the end of the summer Croft, who with John Brown had already formed what was one of the first rock and roll production houses, Extra Sensory Production (ESP), offered Lamb a job. “He was our first employee,” Croft says. There the young Lamb worked parties, debutante balls, and the liquid light shows popular at the time. In December of 1969, Croft was asked to put together an English crew to do some Rolling Stones shows in London, which were followed by a 1970 Stones tour in Europe. It was on that tour Lamb met another influential mentor, recipient number three of this award, Chip Monck. Lamb would go onto work on every Stones tour up to and including 1989’s Steel Wheels.

The earliest large tours put the industry through some growing pains, as those were the days of “making it up when you went along,” Lamb says, and that 1970 Stones tour was a game-changer because of its relatively sophisticated production values. It featured four common spotlights and two Strong Gladiators (the big brother of Strong’s Super Troupers). Those Gladiators were prototypes that came in wooden boxes and were hard to manage. That tour also had other problems. For the Paris show, they realized that the country ran on Delta power (an old power system also found in Belgium and The Netherlands). Lamb, not being a trained electrician, tried to make it run on 110 Volts and “blew a 200A fuse box right off the wall. I got a few serious shocks from that!” So, after he “nearly killed himself a couple of times,” he learned to first use a multimeter.

The success of that tour immediately thrust Lamb into the big leagues, and suddenly the 21-year-old was working Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, Moody Blues, and Emerson Lake & Palmer on major European tours. “There was an avalanche of customers because ESP was the only game in town. We were cobbling this stuff together as there was no formal training for any of it. We just did whatever we had to do.”

Trucking Through America

Lamb at this point thought while he had been to America twice as a lighting director for Steven Stills’ 1971 and 1972 tours, he had yet to see America beyond the insides of planes and Holiday Inns. Meanwhile, future Parnelli Audio Innovator Lifetime Achievement honorees, brothers Gene and Roy Clair, were seeing their concert touring audio business much in demand and “they were desperate for people, so I thought I’d see America in a truck.” The Londoner found himself at their HQ in humble Lititz, PA, and drove one of their trucks for seven months. (And while it’s hard to fathom now, one didn’t need a driver’s license to drive those big rigs in those days.) So off he went with the Moody Blues with Gene mixing for the band. He enjoyed the experience, even when in certain places he had to stuff his long hair in a cap because the people working some southern venues “didn’t want hippie truck drivers around.”

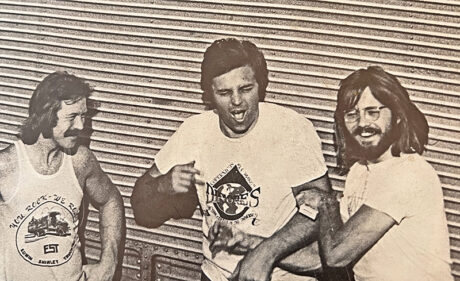

In 1973, Lamb was called home for another Stones tour in Europe and found himself working with another old pal from the Youth Theatre, Edwin Shirley, who at the time was working special effects. “That’s where Edwin tried to kill people with bombs and flashes and stuff like that,” he jokes. But one thing was painfully obvious to both: the transportation aspect of rock and roll touring was abysmal, and they thought they could do better. In 1974, they formed Edwin Shirley Trucking, the first live event trucking company in the world. “The deal we had was since it was called Edwin Shirley Trucking, I got to choose the company colors,” Lamb says. Thus, it was Lamb behind what became the iconic yellow and purple, “the two most garish f**king colors I could possibly choose.”

That was a big year for him, as while the pair was putting that business together, he was still with ESP and went out with Genesis, Pink Floyd, and ELP, handling trucking and lighting. Also, American bands continued coming over in droves, and Monck was persuading them to carry their own production gear from town to town rather than rely on whatever they found in whatever theater they were playing. He threw that business to ESP, which contributed to the company’s explosive growth. To keep up with the demand for bigger shows, ESP was implementing increasingly advanced trussing. And that was also the year when circular screens with Xenon rear projection were employed for the Pink Floyd tour. Lamb tells how lenses had to be ground in France, which allowed them to throw a 32’ image from 14’—something most people at the time thought was impossible. “The two lenses were so heavy it took two people to lift them,” Lamb says.

An Elephant, a Truck, and Other Stories

On the list of unusual asks, surely a baby elephant is near the top. “The Rolling Stones were doing major outdoor shows and were in Memphis on July 4, 1975,” he says. Mick Jagger had decided it would be a good idea to ride a baby elephant on stage wrapped in an American flag. “So, we went and found one, from the circus or somewhere, and used a pallet to lift it on to the stage. Mick came out and had a little ride around on it that afternoon.” But then a wet blanket by the name of Keith Richards showed up and said, “That f*cking elephant goes on stage over my dead body.” A loud “conversation” between the two ensued right there and was getting so out of hand, Lamb suggested they both take it back to the dressing room. Alas, Richards’ view prevailed, and there was no baby elephant at that or any other show.

By the following year, Lamb had returned to England to focus back on trucking as the flow of American bands touring Europe continued to increase. Lamb was in demand and was the lead trucker for almost all the major acts. “All the American bands were having bigger productions, but they had never toured Europe before and didn’t know what they were doing.” In addition to trucking the bands to gigs, once at the venue, he ended up also being their stage manager/production manager—unpaid.

Lamb’s trucking skills are legendary—he’s still known as the only driver who could back a truck into the notoriously difficult Olympiahalle in Munich. To get to that loading dock, a long circular ramp had to be negotiated, and a misjudgment by even a couple of inches risked ruining the delicate Olympic wooden bicycle track that was precariously close to that ramp. “There wasn’t a straight inch anywhere,” he says. But there he was with a truck of Santana’s gear, eyeing it, and then proclaiming to the hall’s host that he could do it. He was told it was impossible, and extra hours must be spent hand-carting all the gear down instead. Lamb ignored that advice and pulled it off.

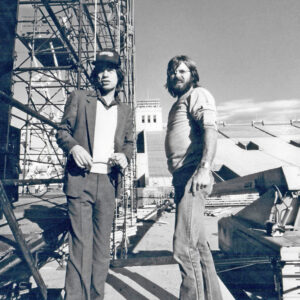

In 1977, he took break from trucking to go with Emerson Lake and Palmer on an American tour, where he worked with Mike Brown Grandstands (recipient number two of this award). For the 1976 movie A Star Is Born, Brown had built a large portable stage that was strong enough to support a load of gear and still offered good sightlines. It was immediately adopted by touring bands, including that major ELP tour. “It became the standard touring roof for outdoor shows because it was load-bearing with steel towers and an aluminum roof,” Lamb explains. Still, the P.A. and lighting rigs kept getting heavier, and while there were many close calls and the occasional minor accident, “no one got killed”—quite the ringing endorsement Lamb gives the staging technology of the day. But the knowledge and experience he earned put Lamb at the forefront of the next live event industry advancement.

In 1981, Fleetwood Mac’s production manager Chris Lamb (no relation—and yet another recipient of this award, in 2015), was in Europe and a lighting rig was too heavy to hang on any existing European roof. In anticipation of this, he brought a Mike Brown roof with him. He put a call in to Roy Lamb and said that there was a roof in a container on the way to Munich. “Build me a stage and some support towers and I’ll see you next week,” the younger Lamb told Roy. Thus, Edwin Shirley Staging (ESS) was born to develop the growing outdoor staging business in Europe.

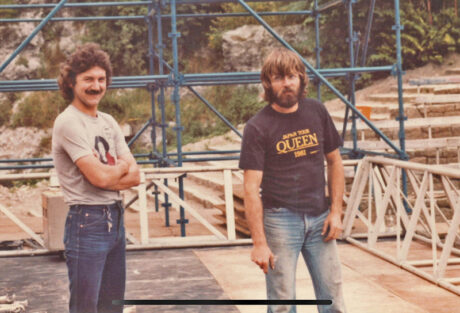

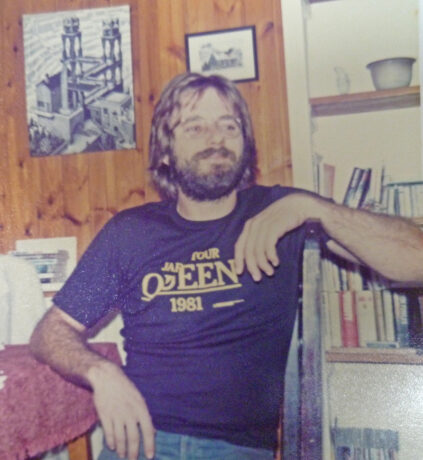

Also that year, Roy Lamb was one of the pioneers, along with 2007 Parnelli Lifetime recipient Gerry Stickells and Rick “Parnelli” O’Brien, who opened the South American market to rock with a massive Queen tour. “It was a real challenge,” Lamb says. “We took a roof and a lot of towers, with the stage having a massive lighting rig.” It was a huge success and a watershed moment for the industry. Lamb would have other Queen moments, including the emotional final show with an ailing Freddie Mercury at Knebworth House in Hertfordshire in 1986, and “it was an absolute stonker [impressive],” he recalls. “There were 140,000 people, and everyone was in Freddie’s hand.”

In 1986, Lamb decided to step back from the trucking and staging business and concentrate on production management. In the years that followed, in addition to the Rolling Stones Steel Wheels and The Who shows, he also fit in tours for acts including Eric Clapton, Peter Gabriel, John Mellencamp, Traffic, Robert Plant, R.E.M., the Cars, Sheryl Crow, and Bryan Adams. He was production manager for the Jimmy Page and Robert Plant No Quarter world tour of 1995, which included doing two shows in a day in a sports arena in Mexico City. They finished the first show and walked off, returning to their dressing rooms. “Now they don’t do encores, but after the first show, not one punter left,” Lamb says. The band had gone back to the dressing room, got changed and Lamb went back and explained that because no one was leaving, they must go back out and do an encore. “Zoom, they went out there and they did the song ‘Rock and Roll’—which they had never done live on that tour. They had rehearsed it a few times, but never played it live.” The crowd went wild, and “then the punters left. And we did that song every night after that. Thinking about it brings the hair up on the back of the neck.”

Some Catching Up

“Huge congratulations to our friend Roy for everything he has achieved in his lifetime,” says Lighting/Production Designer Patrick Woodroffe. “He has multi-tasked in trucking, staging, production, and stage management, and has done so in each discipline at the highest levels. He is the fount of all knowledge of the road. Nothing fazes him because over the years he has seen it all. He is the consummate professional while making it all seem like a game to be enjoyed; and he has done all these things with a constant smile on his face. Roy is a star and so well deserves this award!”

His secret to longevity in this ego-fueled business? “I’m brutally honest to the artists,” even those “who would wind me up a bit.” One who did a bit of the latter was Bryan Adams. Lamb would go into his dressing room and explain that they had an issue, like the next show’s venue couldn’t accommodate the B stage. “I would explain in detail why, and the next show would come, and he would call me into the dressing and ask about it again. ‘I told you about this the other day!’” It happened often enough that Lamb got into the habit of going into the production office, writing the issue down on paper, and making Adams sign “the f*cking piece of paper which I then kept in my pocket. And he stopped harassing me after that.”

He would have retired already but apparently Pete Townshend and Roger Daltrey won’t let him. In 2016, the conventional wisdom was that their The Who Hits 50 tour was going to be their last, and he told the pair then he was done after that one regardless. “Well, we’re not going to do very much more,” they told him. “Why don’t you just fade out gently with us?” Lamb pauses and then says with a smile, “Seven years later, I’m still trying to fade out!”

The Who’s 2022 tour included a stop in Cincinnati, the first time the band returned to perform a show in that city since one of concert touring’s biggest tragedies, which had shaken the industry more than four decades earlier. On Dec. 3, 1979, at the Riverfront Coliseum in Cincinnati, a crush of concertgoers outside the Coliseum’s doors resulted in 11 deaths and many injured. “It was quite moving,” Lamb says of that tribute-filled show staged at TQL Stadium on May 15. “The families [of those killed] were there, and they showed pictures of those that were lost on the screen. It was tasteful and was cathartic for the band and the families.”

Today, Roy Lamb’s priorities include golf, travel, and time with his wife Jenny. “That’s what every roadie who spends their life touring needs to do—catch up. I missed my whole life. I missed my daughter growing up. I missed everything being on the road.” He adds that while he’s officially been to more than 100 countries, he would like to travel at a pace that would allow him to see some of those places.

“I can’t say I hate music—it has given me a very good living,” he says. “But it’s the technical aspect, the logistic side that interests me much more than the music, so I’ve been very lucky that the bands I work for are real musicians.”