The concept of unity gain is deceptively simple: when the output level from a device is equal to the input to that device, you have achieved unity gain. It’s like a high level of Audio Zen, only better. When we say “device,” we can be referring to a hardware device or a plug-in — the concept applies equally in the analog and digital domains. The problem is that most “devices” are intended to mangle audio in some way or another, and that’s where simplicity goes out the window. Let’s look at a few examples.

1: No Compression

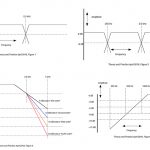

Fig. 1a (above and top) shows Waves’ H-Comp plugged in on a kick drum. The ratio is set at 1:1 and the threshold is very high — meaning there will be no compression. Output level is set to 0. The buttons above the meter allow the meter to indicate input level (“In”), gain reduction (“GR”) or output level (“Out”). The meter is currently set to read Input, and the level is -12 dBFS.

Fig. 1b (above) shows the same plug-in, except the meter has been switched to Out. Notice that the output level is the same as the input level: -12.

Fig. 1c (above) shows the meter switched to GR. There is currently no gain reduction, so the meter reads 0. At this moment, our H-Comp is set to unity. Output level is equal to input level.

2: Compression Added

But why do we use a compressor in the first place? To compress our kick drum (duh…). Look at Fig. 2a (above). The threshold has been changed to -31 and the ratio is around 5:1. The meter is set to In and the input level is the same as it was in the first example.

Fig. 2b (above) shows the meter switched to GR, and since we’ve lowered the threshold and increased the ratio, we are now getting about -6 dB of compression.

If we switch the meter to show output level (Fig. 2c, above), we’ll see that we have lost about -6 dB — which is perfectly normal due to the fact that we are applying gain reduction to the signal. We no longer have unity gain.

Fig. 2d (above) shows how to correct this: use the output level control to “make-up” the difference caused by gain reduction (that’s why some compressors call the output control “make-up gain”). Unity has been restored and the universe is safe once again.

3: Restore to Unity

Things get a bit complicated when there’s more than one processor on a signal. If I plug in an SSL EQ after the H-Comp (Fig. 3a, above) with H-Comp still set to unity, and no EQ dialed in, we can see that the output of the EQ is Zen with the input to the H-Comp — the entire chain is still at unity. If I did not “make up” the lost gain from H-Comp, the output of the SSL EQ would be very low. Of course the reason for using the SSL plug is to EQ the sound (duh again).

Fig. 3b (above) shows what happens to the output level of the SSL EQ plug in when I dial in a lot of low-end: the output is clipping, giving me a distorted kick drum.

Fig. 3c (above) shows the output level control (the white knob next to the meter) turned down, restoring the meter to unity and eliminating the distortion (note the peak hold LED is still lit).

4: Break a Few Rules

No one says that we have to play by the rules here. I could intentionally overload the input of the EQ to create distortion. Fig. 4 (above) shows the H-Comp’s output level cranked, and the output of the EQ turned way down. The chain overall is still at unity, but the output of the compressor is overloaded, creating distortion. The channel fader still tracks in a normal manner (in the middle of its throw) so I don’t sacrifice any flexibility in creating my mix. Sometimes you gotta know the rules in order to break them!

Steve “Woody” La Cerra is the tour manager and Front of House engineer for Blue Öyster Cult.